Jo Deeming's Canterbury Tales of the Unexpected - Turning Site Safety into a Public Experience

The prospect of closing a landmark building for essential repair and maintenance work can present a financial headache, especially if the building relies on entry fee or membership revenue as a vital source of income. Purcell Partner, Jo Deeming, explores how to turn a restoration challenge into funding opportunities that can enhance, rather than diminish the public experience.

Reviving our historic buildings brings unique challenges in many areas, not least of which is site management. For example, for the UK’s retrofit agenda almost every architecture practice and contractor should find their portfolio shifting from mostly new build to a more balanced ‘retrofit and reuse’ approach. This means they will need to get to grips with safe working on sites that remain in use throughout. Conservation can provide some much-needed guidance about how this can be achieved.

The basic principles remain the same on any construction site – to ensure that a project is safe to build, use and maintain. For new build projects, site management is established at the beginning of the process and can be planned using data and lessons carried over from similar projects. With conservation, or any retrofit or reuse project, the site is already live and will present an exclusive set of circumstances. It is here that experience in working on existing sites is essential. Many of these projects are as bespoke as any new design and often without precedent, but come with a distinctive story that invariably makes them as complex as they are valuable.

Whilst working on ‘live’ operational sites brings its own challenges, it can also present opportunities to do things that seem practically impossible and can sometimes facilitate innovations for the visitor experience. Some of these result in examples where the challenges have been great but have been overcome through an innovative approach. This has certainly been the case with the ‘Canterbury Journey’ project based at the city’s cathedral, one of the oldest Christian structures in England and part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The basic principles remain the same on any construction site – to ensure that a project is safe to build, use and maintain

—

Diversifying at height

Working at height is one of the most dangerous factors to consider on a conservation project. As Surveyor to the Fabric at Canterbury, it is my duty to protect and safeguard the fabric of the building, whilst making sure the building does not present a risk to the public and the cathedral community.

Our work at Canterbury Cathedral often involves accommodating teams of skilled craftspeople high above the ground. As part of Purcell’s repair of the cathedral’s nave vaults and nave clerestory windows, we faced the dual challenge of creating a safe place for conservators to work at considerable height, and the need to protect the worshippers, tourists and staff in the busy space below. A safety deck was installed, providing unrestricted access to the works site from the compound on the building’s exterior, and to avoid any potential for permanently harming the fabric, this deck was suspended across the nave from existing apertures.

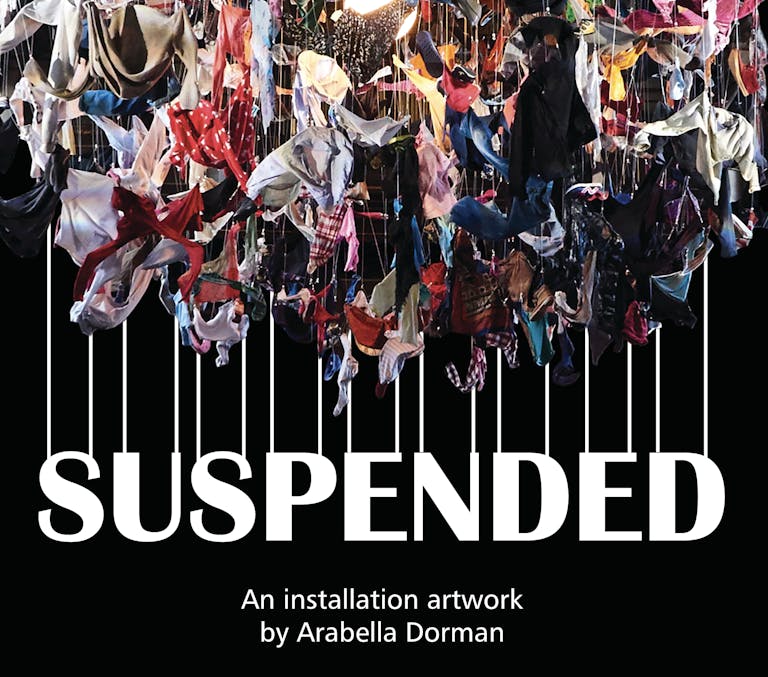

Rather than attempting to hide the enormous scaffold, or to disguise it with a costly photo reproduction of the vaults, we designed something that was intended to be seen – a new, temporary canvas capable of hosting artwork while also matching the imposing magnificence of the cathedral. Arabella Dorman’s evocative artwork Suspended (highlighting the plight of refugees by hanging from the scaffolding the items of clothing they had discarded when boarding boats bound for mainland Europe) headlined these installations, and was described by The New York Times as our “most talked about contemporary artwork”.

Seeing opportunities in the scaffold

Purcell’s work programme at Dyrham Park provides another example of how with care safe scaffolding can be made a positive feature of a programme of works.

The National Trust’s Dyrham Park estate in Gloucestershire, built in the late 17th century, comprises is a Grade I-listed Baroque country house, an orangery, a stable block and a church all set in an ancient, landscaped deer park of over 105 hectares. In 2013, we were commissioned to undertake a £4.2m programme that included re-roofing and masonry repair works, internal reservicing, conservation and repair to the orangery, and the installation of a new biomass boiler plant.

A stipulation from the client was that Dyrham would remain open to the public throughout, and that public activities and educational opportunities would be woven into the programme.

We knew that overhauling the roofs and refurbishing the orangery would, of necessity, both require scaffolding. The roof was 150 years old and the new roof would be expected to last just as long, so it was unlikely that the opportunity for such a significant task would arise again in any of our lifetimes.

Scaffolding is an obvious obstacle to any visitor attraction, but there was no way of avoiding having it on the site – and lots of it. Our thoughts therefore turned to considering whether the scaffolding could become part of a new, temporary, visitor experience. It could be used to give visitors the rare opportunity of seeing in action the work needed to first take apart a large and complex roof, and then to make it weather-tight and secure for the future. In this way an ‘undesirable’ scaffold could be flipped into an enhanced visitor opportunity and a revenue stream.

Planning meant holding extensive consultations with scaffolders, contractors, the Building Inspector and the Trust’s insurers, all at pre-tender stage, to resolve how the ambitions for keeping the site open and allowing visitors to see works in operation could be safely achieved both in terms of practicality and compliance.

After looking at various possibilities, it was decided that the best solution for the re-roofing would be to supplement the internal working scaffold by adding a second outer scaffold for the public, allowing them to observe the works as they progressed without hindering that work or causing health and safety concerns. This was achieved by installing an accessible, solid, wide walkway with passing points, fully accessible via a lift. Made up of five hundred tonnes of scaffolding, the structure was entirely freestanding and was fixed into the ground with mini piles, to remove the risk to the fabric from tying it to the building. It was modular, so that the sections could be assembled on the ground and then craned into place. The final scaffolding covered an area 47.5m long and 38.2m wide, large enough to allow the restoration teams to carry out their work safely and comfortably, and protecting them and the roof from the weather.

Site huts were positioned at the base of the scaffold to equip visitors with PPE, and to collect waiver forms. The contractor provided a visitor guide and programmed ‘meet the builder’ days for students and local colleges to run alongside existing apprenticeship and training programmes. Purcell’s team provided student placements and work experience along with a programme of expert talks for the public.

For roof slates that had reached their end-of-life, visitors were given the opportunity of naming or adding messages into the replacement tiles in return for a small donation.

The scaffolding erected above the orangery also included a promenade loop twenty-five metres above ground, enabling visitors to see the conservation works in action and engage with the contractors, who ran daily question-and-answer sessions and demonstrations.

Whilst catering for visitors added complexity - and meant more expensive scaffolding was needed - the extra dimension to the visitor experience helped to recoup a significant amount of the overall scaffolding spend. When the public access opened in 2015, it generated a good deal of press and media attention, and further enhanced the fundraising potential of the venture. Visitor numbers increased, as did donations and footfall across the park’s estate.

Securing structures safely

Not all health and safety actions on working sites can be planned in advance. In 2009 an unexpected event at Canterbury Cathedral called for swift action both to prevent immediate further damage to the building, and to protect the public and cathedral team.

A sizeable lump of masonry fell from the Great South Window, providing a dramatic indication that something was seriously wrong and raising the most serious health and safety concerns for the many visitors and staff on site. Not only was the window extremely high and a potential risk to anyone working on it or walking below it, but it was also spiritually, culturally and historically precious: the stonework was the frame for some of the most important medieval stained glass in the world (elements of which date from the 12th century). The stakes for caution could not have been higher.

Urgent investigations soon revealed cracks in the stonework and evidence of incipient widespread structural failure. Following emergency consultation with ecclesiastical and heritage bodies it was agreed that the stained glass could not remain in the decaying stone frame, and needed to be urgently removed to safe storage. The frame itself would have to be dismantled and rebuilt, salvaging as much of the original stone as possible, with rebuilding where necessary, using traditional materials and techniques.

Dismantling and reinstalling the towering window (16.8 metres high and 7.5 metres wide) required careful planning to ensure the safety of the public, of the conservation and cathedral teams, and indeed of the building itself.

The first stage was to build a frame on either side of the window, effectively sandwiching the historic masonry between scaffold towers so that no more parts of the window could fall, and allowing conservation specialists to access and survey the window safely.

We ascertained that the upper tracery remained in relatively good condition, and working on the conservation principle of ‘as much as necessary, as little as possible’, we began by asking whether we could devise a method to retain the tracery in-situ while we were underpinning with new masonry below. This concept was developed using with finite element analysis, structural temporary works designs and physical prototype formwork that enabled us to physically test the concept in advance of formal applications for consent.

Through this process we learnt that the pursuit of minimal intervention, while technically possible, would increase the risk to the workforce and potentially to the longer-term surety of the fabric.

The support scaffold meant that access to the window was restricted. On the one hand, it provided accessibility for the restoration team, but on the other it presented an obstacle to the conservators. To replace the lower tracery without full dismantling would mean that cleaning, setting out, measuring, protecting, dismantling, repairs and reinstallation would all have to be undertaken by the cathedral’s masons and glaziers working entirely by hand in a constrained space. Moreover, with many of the stones above their heads weighing more than 250 kilograms, and some as much as half a tonne, failure could prove catastrophic.

Weighing health and safety against the presumption for minimal intervention, it was eventually agreed between us and the authorities that a full dismantle and rebuild of the window was the correct approach.

Our future understanding of preservation

It is evident that the correct approach to health and safety on working sites must be bespoke: as ever with conservation, there are no one-size fits-all solutions. Increasingly we are finding great benefits in marrying traditional knowledge of materials, techniques and methods with innovative technology like Building Information Management (BIM). BIM is an essential part of our heritage conservation work on many of our current projects, including Manchester Town Hall and the Elizabeth Tower (Big Ben).

It is the ‘I’ for information we find to be the most important value, not least when it comes to site safety. In the past, the way we maintained and passed on information from one generation to another was by handing on niche skills and know how. In my own case, at Canterbury my work has been greatly facilitated by having a first-hand relationship with Canterbury’s previous Surveyor to the Fabric, which allowed me to acquire knowledge handed down for generations about the characteristics and sometimes eccentric behaviour of specific materials in the particular conditions of the Cathedral. But the relationship at Canterbury is the exception. In its absence, by using BIM Purcell are better able to record and preserve incredibly precise information about a historic building, and we hope this will serve the buildings well in the future. Properly employed, BIM can record what lies beneath the surface of our completed works. This can then be augmented with further innovations and discoveries. Precisely mapping and recording what we know about buildings, their individual materials and construction, and their distinct environments will help us care for and protect our heritage into the future.

In the realm of Health and safety, BIM provides an opportunity to record not only fabric condition and remedial actions, but also observations about how we went about the work and why. Armed with this information, our successors will have the best possible chance of ‘standing in our shoes’, and making informed decisions about how and where they will intervene safely. As conservation professionals we can then avoid the perils of misinterpreting the urgency of matters of building and structure safety in terms of condition, whilst still ensuring we are not complacent in our other duties as professional advisors: not least the safe operation of our buildings for both our professional colleagues and the general public.